Investing in cryptocurrency-funded projects is as hot as ever, and the almost complete absence of success hasn’t seemed to dim investors’ hopes one bit. In 2017 — with more than a full quarter to go — various project ICOs (that’s initial currency offerings) have already raised about $1.7 billion.

There aren’t too many successful projects to speak of, but investors remain optimistic, and cryptocurrencies like Ethereum may help explain why.

TOP-5 cryptocurrency capitalization and prices. Source

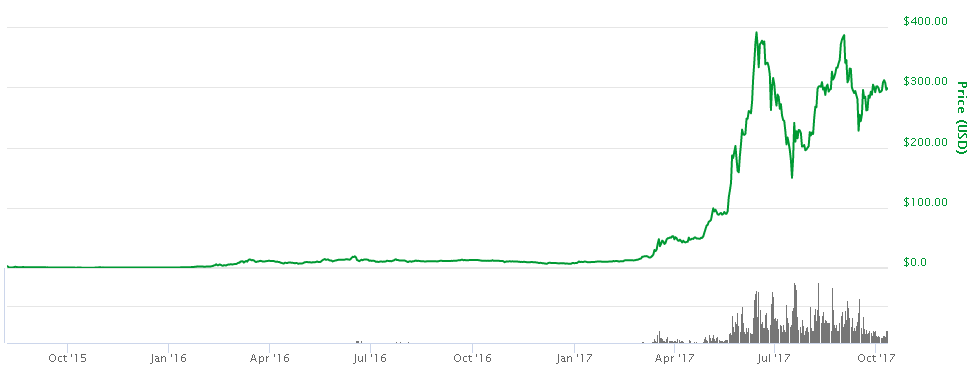

As you can see from the capitalization table above, Ethereum is a distant second to Bitcoin but miles ahead of other altcoins. In June 2017, the upstart almost overtook the mighty Bitcoin. What makes Ethereum so special, and why is it at the heart of the vast majority of ICOs this year?

The idea of Ethereum

From a user’s point of view, Bitcoin is nothing more than a payment system: Users transfer money to one another, and that’s about it. Ethereum goes beyond the simple payment-system framework, giving users the ability to write wallet-based programs.

These programs can receive money from wallets automatically, decide how much to send and where, and so forth — with one important condition: Each program operates the same for all users. The programs act according to known principles that are predictable, equal, transparent, and unmodifiable. Ethereum wallets come in two types: those managed by people and those run autonomously by programs.

The programs, also known as smart contracts, are written to the blockchain. Thus, a contract is stored forever, all users have a copy of it, and it is executed equally for every network participant that deals with it.

This innovation has significantly expanded blockchain currencies’ scope of application.

Examples of smart contracts

What programs can be written? Any you like. Take, for example, a financial pyramid. A pyramid’s smart contract might use the following rules:

- If sum x arrives from the address of wallet A, log it.

- If after that, sum y > 2x arrives from address B, send 2x money to address A, and log the debt to participant B.

And so on for each user and transaction that follows. Optionally, a rule could send 5% of all incoming money to the author of the smart contract.

Or how about an auction?

- If the auction is not over, log the addresses and bidding amounts of each participant.

- When the auction is over, select the maximum bid, announce the winner, and return all other bids.

Endless combinations of other entities and applications are possible: wallets with multiple owners, financial instruments, self-placing bets, polls, lotteries, games, casinos, notaries, and more.

Because of the blockchain, everyone can be sure that no one is cheating; everyone sees the program’s code and can track it working exactly as written. It will not make off with anyone’s money or go bankrupt (assuming, of course, there are no bugs or gremlins in the code).

Limitations of smart contracts

The smart contracts do, however, have significant limitations. Here are some of them:

- It’s very difficult to produce random numbers in a blockchain-based program, which affects lotteries.

- It’s not easy to hide certain information in blockchain — for example, auction participants or their bids. Blockchain was designed for transparency and sometimes it turns into disadvantage.

- If the contract requires information that is missing in the blockchain (e.g., the current exchange rate of a particular currency), then you have to trust a person who is adding this information to the blockchain.

- To interact with the contracts, users need ethers — the internal currency of Ethereum. Users without money wallets cannot take part in polls or any other Ethereum-based activities.

- Smart contracts work slowly. About 3 to 5 transactions per second can be performed worldwide — in total, not per participant.

- Any error in a smart contract stays forever. The only way to fix an error is to switch to another smart contract. However, this option must be included in the initial program, which is rarely the case.

- Smart contracts can freeze or fail to work as expected because program code can be difficult to understand, so writers may make critical errors — and users may not be able to tell what the code will actually do.

A simple Ethereum smart contract. Can you see the error that makes it possible to steal all of the money? Neither would most people.

Ultimately, much depends on the capabilities of smart contracts’ authors.

The main use of smart contracts

Pyramids, polls, casinos, lotteries — what’s not to like? But what smart contracts have really facilitated is IPO-style fundraising.

First of all, a smart contract lets you automate accounting. The contract logs how much money comes in and from whom, computes and distributes “shares,” and enables each participant to transfer and sell those shares.

Second, there’s no need to mess around with e-mail addresses, credit cards, card verification, investor authorization, and the like.

Finally, everyone can see how many shares were issued and how they were distributed among participants. The blockchain protects participants from project owners issuing additional shares secretly or someone selling one share multiple times to different people.

ICO — initial coin offering

As of January 1, 2017, one ether was worth $8, and the value peaked (for now, at least) at $400 by June. Gains were thanks to the large number of ICOs held as the initial offering of shares in startups. The desire to speculate in projects stimulated demand for the cryptocurrency — in this case, Ethereum. And such projects are now legion.

Ethereum price chart. Source

The typical cryptostartup follows this pattern:

- You have an idea, typically something cryptocurrency or blockchain related.

- You need money to get things off the ground.

- You announce to the public that you’re accepting ethers in exchange for shares (or tokens or whatever) under a smart contract.

- You advertise your project and raise the required sum.

The amount raised is usually $10 to $20 million, and it takes somewhere from a few minutes to a few days to collect. Typically, the ICO is limited in terms of time or amount raised, which causes a feeding frenzy.

Sometimes the frenzy reaches comic proportions. For example, one project ICO raised $35 million in 24 seconds. To get their fingers in the pie, project diehards paid up to $6,600 commission per transaction; the high demand for Ethereum combined with its low throughput hiked commission fees.

Crypto-investment payback

What happens next with tokens issued to investors depends on the project. Someone might promise to pay dividends on future profits; someone else might plan to accept the tokens as payment for project-related services. Another entrepreneur might promise nothing at all, like the Useless Ethereum Token‘s creator did, explicitly declaring that nobody gets anything in return and raising about $100,000 nevertheless.

Generally speaking, the tokens find their way onto the crypto–stock exchange, where they are traded. Those who missed out on the ICO can buy them there on the exchange, usually at a markup. Those who took part in the ICO in hopes of reselling at a profit can offload them on the exchange, where the regular economics of supply and demand apply (despite there being no product). One difference, however, is that no regulators exist in the crypto-industry, so shady means of inflating prices run rampant.

As I said at the beginning, there seems to be no more reason to jump into the ICO trend than any other get-rich-quick scheme — but now you understand some of the tech wizardry behind the excitement.

BlockChain

BlockChain

Tips

Tips