HTTPS certificates are one of the pillars of Internet security. But it is not all roses with them. We have already discussed the ways the existing system often fails to guarantee security to users. Now let us focus on what can go wrong for the website owners.

Two valid certificates for the same domain

Domain registration and HTTPS certification are often controlled by different organizations, so the validity periods for domains and certificates will not necessarily be the same. That leads to situations in which the former and the current owners hold valid certificates for the same domain at the same time.

What can go wrong in a situation like that, and how widespread is the problem in real life? At DEF CON 26, researchers Ian Foster and Dylan Ayrey presented their study of the problem. According to them, there are even more complications than seen at first glance — and it’s a surprisingly widespread problem.

The most obvious problem is just what you might expect to happen if someone else holds a valid certificate for your domain: a “Man-in-the-Middle” attack on the users of your website.

Foster and Ayrey used the Certificate Transparency project’s certificates database to identify 1.5 million certificate cross-ownership problems — which amounts to almost 0.5% of all Internet sites. In one quarter of these cases, the older certificate is still valid, which leaves 375 thousand domains vulnerable to the Man-in-the-Middle.

But that’s not all. It is quite common to make one certificate for multiple domains — easily dozens or even hundreds of them. For example, Foster and Ayrey were able to detect a certificate covering 700 domains at the same time, and as the researchers say, this list includes several very popular domains.

Not surprisingly, some of those 700 domains are currently up for grabs; therefore, anyone can get one of them registered and get an HTTPS certificate for it. Now the question is, does the new domain owner have the right to revoke the previous certificate to protect his website from a Man-in-the-Middle attack?

Can the certificate be revoked?

Certificates can, in fact, be revoked. The certification centers’ operating procedure provides for certificate revocation if “any of the information appearing in the Certificate is inaccurate or misleading.” Such revocation has to take place within 24 hours of receipt of the notification.

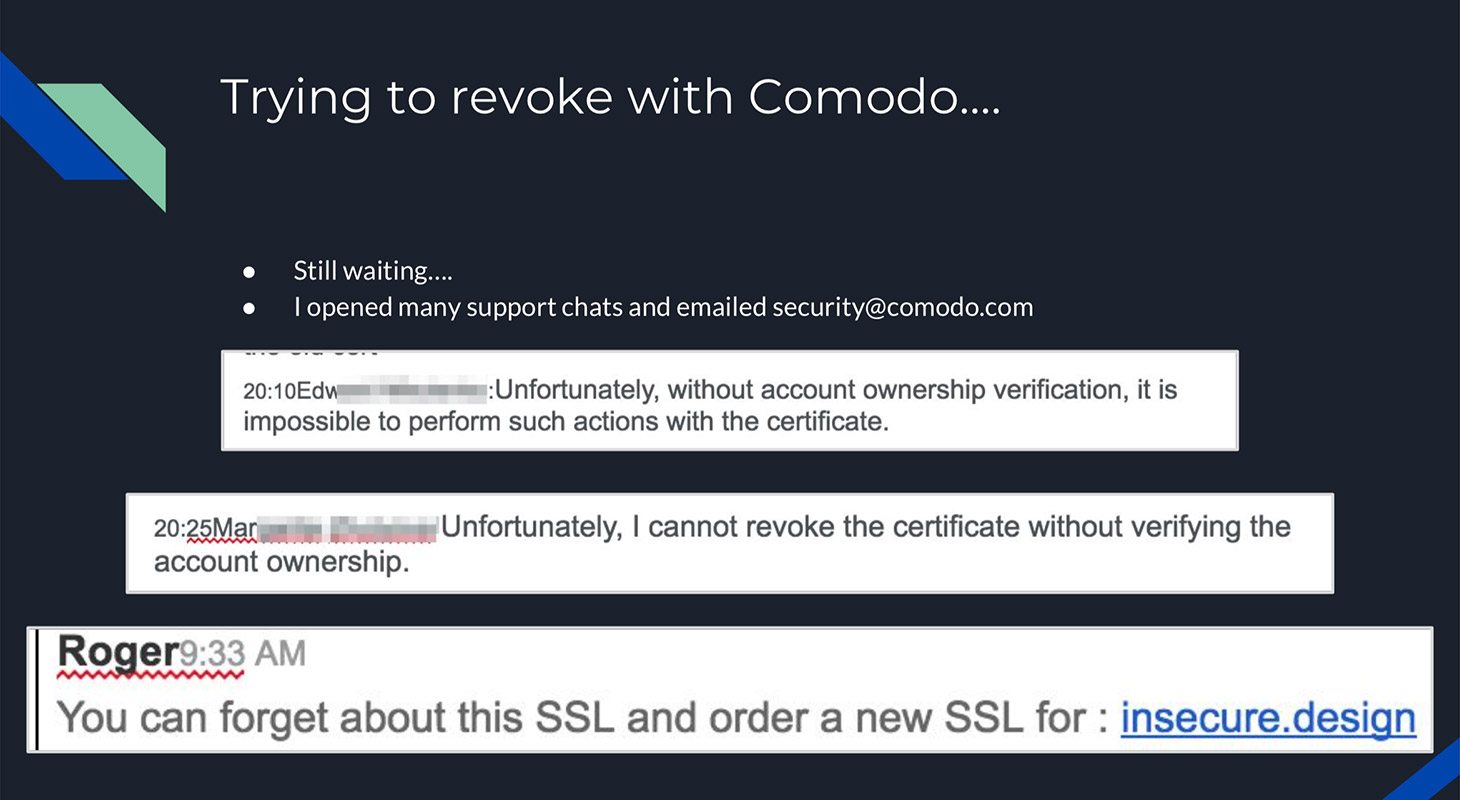

Foster and Ayrey took a look at how that works in real life, and they found that the procedure varies greatly for different certification centers. Thus, Let’s Encrypt employs automated tools that help revoke a certificate very quickly — almost in real time. At other certification centers, you will have to communicate with actual people, so it won’t be so fast. Sometimes, getting a certificate revoked takes perseverance and much more than the specified 24 hours of waiting time. In the worst cases, you may even fail to have a certificate revoked. For example, the researchers’ correspondence with Comodo ended with a suggestion to “forget about this SSL and order a new SSL.”

One way or another, you will have a residual certificate revoked more likely than not. The news is both good and bad. On the one hand, the new domain owner will in most cases be able to protect himself from a Man-in-the-Middle attack that uses the residual certificate vulnerability. On the other hand, it means someone else may purchase a free domain from among those covered by a “shared” certificate and have it revoked, thereby strongly handicapping the use of the associated websites.

How widespread is this problem? Even more so than the previous one: 7 million domains — more than 2% of the Internet! — share their certificates with domains whose registrations have already expired. 41% of the previous certificates are still valid. Therefore, several million domains are currently exposed to DoS attacks that use the certificate revocation vulnerability.

Let us get back to the abovementioned 700-domains certificate. To demonstrate how immediate the problem is, the researchers purchased one of the free domains covered by this certificate. So now, in theory, they have an opportunity to launch a DoS attack on hundreds of active websites.

How to get protected

A total of 375,000 domains are vulnerable to MitM attacks and several million more to DoS attacks through the use of residual certificates. Your domains, too, may be on the list. With the report having been presented at the biggest hacking conference, you may rest assured — someone is already looking for vulnerable domains, even as you are reading this article. But how can website owners protect themselves? Foster and Ayrey suggest these steps:

- Use an Expect-CT HTTP header with “enforce” directive to be sure that only the certificates listed in Certificate Transparency database are trusted for your domain.

- Use the Certificate Transparency database to check if your domains have valid certificates issued to previous owners. You can do this using Facebook’s Certificate Transparency Monitoring tool. To simplify the task, the researchers have offered a tool of their own design that anyone can use to search for domains exposed to the described vulnerabilities.

We can add a few more tips:

- Take a full inventory of your corporate websites to see if there are any residual certificates for your domains. If you find any, try contacting the certification center and ask them to revoke such certificates.

- Do not get one certificate for multiple domains, especially if it is a common practice in your company to create great numbers of websites and associated domains without strict operability monitoring. If the registration for such an “abandoned” domain expires and someone else takes it over, all they will have to do to take down your corporate website is have the certificate revoked.

- Consider the compromised certificate situation in advance. You’ll have to revoke it urgently, and, according to the study, some certification centers are too slow to respond — so it might be a good idea to deal with the faster ones.

def con

def con

Tips

Tips